The Japanese Path to Happiness: It’s Not About Chasing Success, It’s About Cultivating Joy

In much of the Western world, the pursuit of happiness is often painted as a race towards a finish line marked by grand achievements: a promotion, a bigger house, a personal best, a major life milestone. We’re taught to chase success, believing that happiness is the prize waiting for us on the other side. But what if this approach has it backwards? What if true, sustainable happiness isn’t a destination to be reached, but a garden to be cultivated, day by day, through small, intentional practices?

The traditional Japanese perspective on happiness offers a profound and gentle alternative. It’s a philosophy less concerned with the peaks of euphoric success and more focused on finding a quiet, resilient contentment within the flow of everyday life. This approach is deeply woven into concepts like **Ikigai (生き甲斐)**, **Wabi-Sabi (侘寂)**, and **Mono no Aware (物の哀れ)**, which together paint a picture of happiness that is rooted in purpose, connection, acceptance, and an appreciation for the simple, fleeting moments.

This article will explore the Japanese path to happiness, uncovering why it’s not about achieving external success, but about nurturing an inner state of well-being. For women navigating the immense pressures to “have it all” and “do it all,” this wisdom can be a liberating guide to finding a more authentic and lasting sense of joy.

Shifting the Goal: Why “Success” Doesn’t Equal “Happiness”

The problem with linking happiness directly to success is a phenomenon known as the “hedonic treadmill.” We achieve a goal we thought would make us happy, feel a temporary boost, and then quickly adapt to our new reality, our happiness levels returning to their baseline. The goalposts then shift, and we start chasing the next big thing, perpetually deferring our contentment.

The Japanese approach, influenced by Zen Buddhism and Shintoism, intuitively understands this. It suggests that happiness (or a state of well-being, *shiawase* 幸せ) is found not in the arrival, but in the journey; not in perfection, but in imperfection; not in having more, but in appreciating what is.

The Pillars of Japanese Happiness: Cultivating Contentment from Within

Let’s explore the key concepts that form the foundation of this unique approach to happiness:

1. Ikigai (生き甲斐): Finding Joy in Your “Reason for Being”

As we’ve explored before, Ikigai is your reason to get up in the morning. Crucially, this isn’t necessarily a high-powered career or a grand, world-changing mission. The Japanese understanding of Ikigai is often found in the small things:

- Daily Purpose: The joy of tending to a garden, the satisfaction of perfecting a craft, the purpose found in caring for family, or the connection fostered within a community group.

- Process over Outcome: Happiness is derived from being engaged in the *process* of your Ikigai, not just from the final result or the external validation it might bring.

- Action and Contribution: It’s an active, ongoing state. Happiness comes from doing, contributing, and feeling useful, no matter the scale.

2. Wabi-Sabi (侘寂): The Happiness of Embracing Imperfection

The relentless pursuit of perfection is a major source of modern anxiety. Wabi-Sabi offers a beautiful alternative, teaching us to find beauty and contentment in things that are imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.

- Acceptance of Flaws: This applies not just to objects (a chipped cup, a weathered table) but to our own lives and selves. Happiness comes from self-acceptance, not from achieving a flawless ideal.

- Appreciation of Simplicity: Wabi-Sabi finds joy in the simple, the humble, and the unadorned. It teaches that contentment can be found in a simpler life with fewer, more meaningful possessions and pursuits.

3. Mono no Aware (物の哀れ): The Bittersweet Joy of Transience

This concept is about acknowledging the fleeting nature of all things with a gentle, appreciative sadness. It might sound melancholic, but it’s a profound source of happiness.

- Heightened Appreciation: Understanding that a moment is temporary – like the brief bloom of cherry blossoms or a special time with loved ones – makes us cherish it more deeply.

- Letting Go with Grace: Mono no Aware helps us accept the natural cycles of life and change without resistance, fostering a sense of peace rather than a struggle against the inevitable.

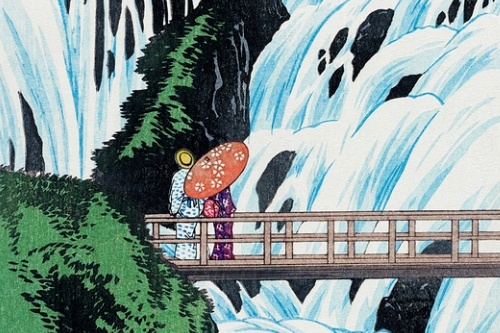

4. Shinrin-yoku (森林浴) & Connection to Nature: Finding Happiness in “Shizen”

The Japanese reverence for nature (Shizen) teaches that humans are part of a larger, interconnected web. Happiness is found in aligning with this natural world.

- Restorative Power: Practices like “forest bathing” are scientifically proven to reduce stress and improve mood. Simply being in nature is a direct path to well-being.

- Grounding Presence: The steady, cyclical nature of the seasons provides a grounding force, reminding us of a rhythm larger than our own immediate worries and ambitions.

Why This Approach is So Liberating for Modern Women

For women, who are often societal barometers of “success” – juggling careers, families, personal aspirations, and beauty standards – this Japanese perspective can be a radical act of self-compassion.

- It Removes the Pressure to “Have It All”: It validates the happiness found in diverse, often uncelebrated areas of life, not just in a high-achieving career.

- It Honors the Journey of Motherhood and Aging: The concepts of Mono no Aware and Wabi-Sabi find profound beauty in the transient stages of life and the “imperfections” that come with age, countering societal pressure to remain eternally young and flawless.

- It Redefines Productivity: Happiness isn’t tied to a perfectly managed to-do list. It can be found in a moment of quiet tea (a mindful pause) or the simple act of tending to a plant (Ikigai).

- It Fosters Resilience: By accepting imperfection and transience, this mindset builds resilience. A “failure” in a traditional success-oriented view is simply part of the natural, imperfect process of life from a Wabi-Sabi perspective.

Simple Ways to Cultivate Happiness, the Japanese Way:

- Identify Your Small Joys: What small, daily activities bring you a sense of purpose or quiet contentment? Make time for them. This is your everyday Ikigai.

- Appreciate an Imperfect Object: Find an object in your home that is worn, old, or slightly flawed. Take a moment to appreciate its history and character. This is practicing Wabi-Sabi.

- Savor a Fleeting Moment: Next time you experience something beautiful but temporary (a sunset, a shared laugh), consciously acknowledge its fleeting nature and cherish it more deeply. This is Mono no Aware.

- Take a “Nature Pill”: Spend five minutes outside without your phone. Simply observe the trees, the sky, the sounds. This is your dose of Shizen.

- Focus on One Task at a Time: Instead of multitasking, bring your full, mindful attention to one simple action, like washing a dish or writing an email. This is finding joy in the process.

Finding Your “Shiawase” (幸せ): A Quieter, More Resilient Joy

The Japanese path to happiness is not about loud, euphoric victories, but about a quiet, resilient sense of well-being that is cultivated from within. It’s about discovering that true contentment doesn’t lie at the top of the mountain of success, but is found in the mindful, appreciative way you walk the path every single day.

By embracing the wisdom of Ikigai, Wabi-Sabi, and a deep connection to nature, we can shift our focus from a relentless chase to a gentle cultivation. We can learn that happiness is not something to be achieved, but something to be lived, moment by imperfect, beautiful, and fleeting moment.